Cool Mom

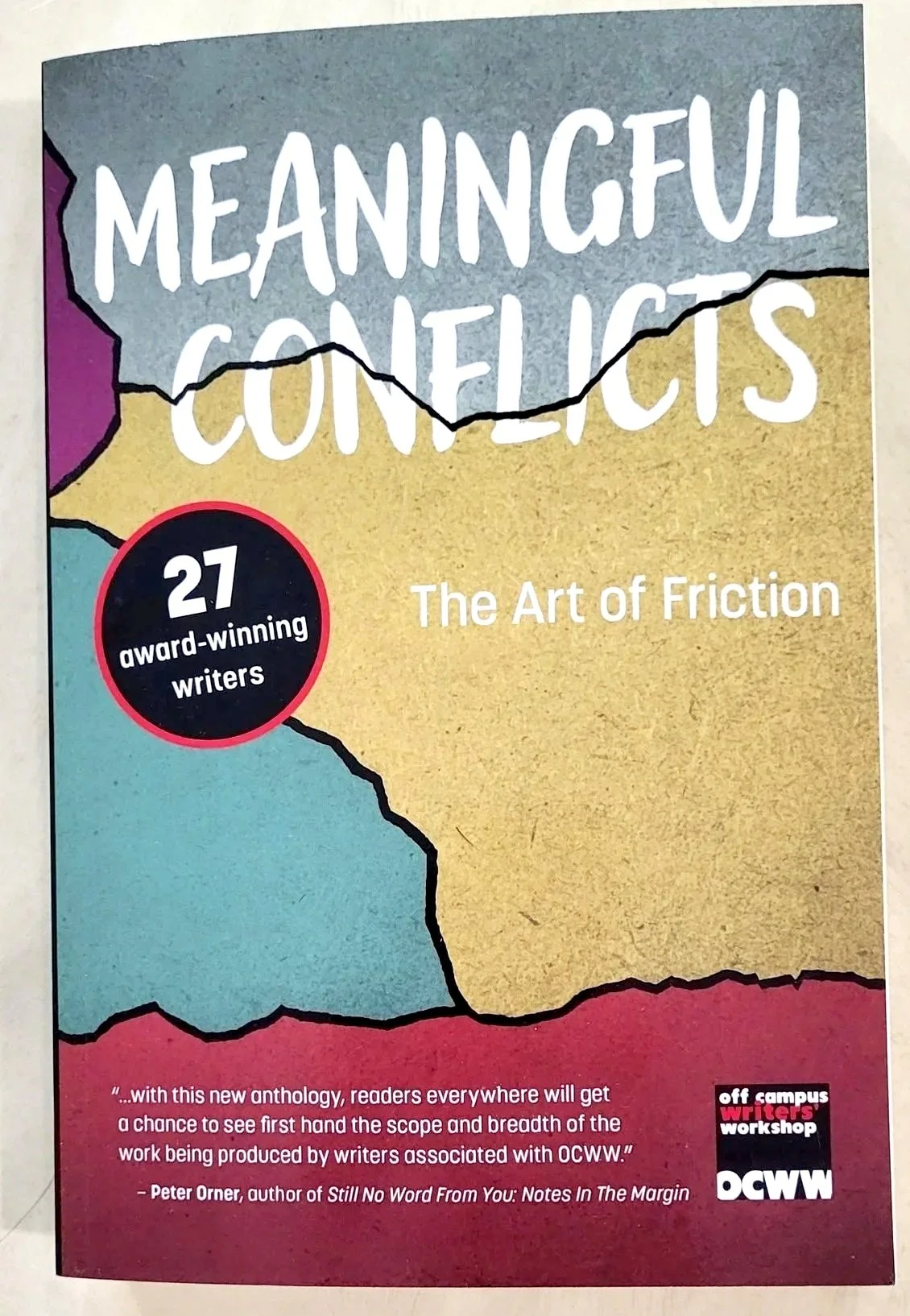

By Rita Angelini

Published April, 2023

In the dressing room of Carson's Department Store, my fourteen-year-old daughter, Marina, twirled for me in a rose-colored satin mini dress, her choice for the homecoming dance. The florescent lights bounced off the sequins and flashed in the three-way mirror-six feet tall, waist-long amber hair, vivid cocoa eyes, looking like a cover girl for Seventeen magazine.

I reached to measure the length of the dress. She whirled and stepped back. "Don't touch my crotch” Marina said.

"It's too short” I said.

"It is not” She placed her hand on the side where her legs joined her torso. "See”

"It looks too short” I said.

"I want this one” Her body stiffened. I expected to hear "I hate you" from my daughter but I held the wallet.

I was not a cool mom.

___________________________

When Marina was young, she was my snuggle bunny, my entertainment, my shadow. She looked up to me with adoring eyes. Her sister-two years younger and born with extreme special needs-diverted my attention away from Marina. We adjusted to a new lifestyle, and though her sister's condition stabilized for a time, the threat of death still loomed.

Marina pitched in, expressing concern that her sister might feel excluded. When Marina went trick-or-treating, she asked for two pieces. She would drop the second piece in her sister's pumpkin and kiss her sister, who waited at the bottom of the stairs in her wheelchair.

Beginning at age four, Marina met with therapists and attended sibling support groups to cope with the challenges that having a sister who required around-the-dock care presented. The goal was to have an established relationship with a therapist in case something went wrong.

We camped, saw plays, and attended concerts. For Marina's eighth birthday, I threw the ultimate surprise bash. Having planned to raze our home and rebuild on the same lot, we invited Marina and her school pals to run wild in the old house once it had been emptied. They went crazy with markers, paints, silly string, shaving cream, covering walls, windows, ceilings, carpets. The party was the talk of the school.

She told me she had the coolest mom ever.

The week before Marina started seventh grade, her sister suffered a violent seizure at a remote campground. As I maneuvered her sister's body to clear her airway, she projectile vomited on Marina, me, and the floor. Eyes wide, Marina stared at the mess on her. The rancid smell permeated the camper. In the hour we waited for medical assistance, her sister's tiny body jerked and thrashed. Marina cried and shook with fear, and her father and I took turns holding her.

I accompanied her sister to the hospital in the main city. My husband drove Marina home to stay with a friend before joining me. Following her sister's medical crisis, Marina talked about restarting her sessions with the psychologist, but the therapist wasn't available and Marina had to deal with it on her own. After this, she hated her therapist and all therapists.

She stopped doing her chores. I nagged: clean your room, empty the dishwasher, scoop the kitty litter.

Her grades dropped. I nagged: turn in your homework, study for tests, complete your school projects.

Not cool mom.

I pressed her about the change in her behavior. She stayed in her room.

I resorted to using money. We paid for homework, test scores, and chores. She excelled.

Cool mom.

During eighth grade, her sister's condition worsened. My energy spent, I couldn't monitor and pay her for schoolwork. I pared Marina's activities except for harp lessons. She seemed at peace when she played her harp for her sister.

Marina refused to believe or blame her sister's situation for her anxiety. We pushed her into family counseling. The psychologist remarked on the change in our relationship from the prior year. Marina sneered at me and told the psychologist she hated me. With arms crossed, Marina refused to talk, so my husband and I talked. We attended four sessions. The psychologist saw no progress with Marina.

Not cool mom.

We bided our time, waiting for her sister's health to improve. It didn't. This time we considered splurging on Marina's Christmas wish list: cell phone, Uggs, cash. I consulted with the psychologist. She didn't recommend it.

Despite that, we purchased the forced pleasantness.

Cool mom. For a while.

In high school, Marina made new friends, joined the swim team, and participated in clubs. Her father and I had a simple rule: no socializing with juniors or seniors. She started a relationship with a senior. We put the kibosh on it. The combined moodiness of a teenager, a new school, and the relentless stress of her sister's condition-three failed surgeries and an experimental surgery scheduled in January-Marina's anxiety increased, with dizziness and chest pains.

Her father suggested Marina see her pediatrician, I suggested she play the harp for relaxation.

"You don't care about me” Marina yelled.

Not cool mom.

Test results from the cardiologist revealed no defect. The pediatrician suggested counseling. Marina refused.

I wanted to be the cool mom again.

So I bought that glitzy homecoming dress from Carsons, while her fifty-pound sister lay at home with 24-hour care, her useless legs down to scrawny toothpicks.

Before homecoming, I arranged for a caregiver so Marina and I could lunch after swim practice at Olive Garden, her favorite restaurant. Marina overslept. I yelled for her to hurry. I carried her sister to the car and put her on the reclined front seat. Marina sat in back, not talking.

''I'll pick you up at eleven” I said, when I dropped her off. She got out and slammed the car door.

When my mom dropped by for a surprise visit, my Olive Garden plans changed. Marina was surprised to see her grandma when we picked her up.

"Grandma and I are going to Olive Garden;' I said.

''All three of us?" Marina said.

"Just Grandma and me”

"Bitch” Marina muttered under her breath.

"Did you hear that?" I asked my mother.

Being diplomatic, she said, "I am sure you misunderstood her. Right, Marina?"

"She heard me” Marina said.

At Olive Garden, my stomach grumbled with the aroma of garlic. I rambled to my mother. I had hoped that my mother would be able to provide perspectivehaving raised nine teenagers herself. But she had no wisdom to share; I was the eighth of nine kids, and my mom was done with teenage attitude.

Marina's task for the day was to clean her room for the Homecoming sleepover I had naively offered to host. Since she hadn't played the harp for her sister in days, when she was finished, I asked for a harp concert. Just thirty minutes. I secretly set a timer. She resisted-but even when her long, elegant fingers plucked the wrong strings, it still sounded beautiful. I closed my eyes and stroked her sister's hair, letting the relaxing notes wash over me. After just two minutes, she stopped playing, breaking the spell. I opened my eyes. She left and came back.

After forty-five minutes and numerous intermissions, I checked the timer. She had played a total of only twelve minutes. Far short of the half-hour her teacher prescribed. I told her I was wasting my money on lessons, and that if she didn't like playing, she should quit.

In tears, Marina stomped out of the family room.

Not cool mom.

Later, I went upstairs to get Marina for an eyebrow waxing appointment I had promised her. I also had scheduled a hair appointment homecoming morning. The rose satin dress hung on the door with three-inch heels below it. "We'll leave in five minutes. Your room looks nice”

Cool mom.

Marina's phone vibrated on the dresser. I reached for it. She lunged and grabbed it. I held out my hand. "Give me the phone”

"It's nobody.” She pulled away.

"Now!"

I glared at her with my palm open, jerking my hand. She gave me the phone. The screen read: "rubs your feet" -from the senior who played on the football team. I scrolled on, and gasped when I read the full text, describing his hands moving up her leg. I couldn't deal with a teen desperate for love coming home pregnant.

The phone weighed heavy in my hand, and I told her she was not going to Homecoming. I took the phone to show her father. He read the messages: lots of idle chit-chat, but also sexting that described long-distance petting, complaints against me yelling at her about swim practice, not taking her to Olive Garden. And the latest: her crazy mother timing her harp practice, heavily laden with the B-word.

Her father shook his head and reminded Marina of the rule that she wasn't to socialize, communicate, or hang out with seniors or juniors. "Number one, you're not going to homecoming. Number two and three will come when I calm down enough to think about it”

Marina cried. I canceled the eyebrow waxing and the updo. She cried some more. I emailed the parents my regrets about not hosting the after-party.

Not cool mom.

The next few days, Marina was repentant, sweet as cotton candy. 'Tm sorry I wrote those things. I didn't mean them. Please let me go” Her father and I propped each other up when the other was close to caving. Even while I dreamed of her perfect evening, we answered with a resounding No.

Homecoming night she sat with us on the couch with popcorn and a new-release rented movie.

Marina continued to spiral out of control. Once during class, a classmate noticed blood seeping through her sleeve at her wrist and reported it to the teacher. Her school required a psych evaluation that night. In the commotion of the ER, under the stark fluorescent lights, with midnight approaching, she refused to speak to the doctors. They signed a waiver to readmit her to school only after my husband explained our other daughter's medical crisis. Doctor's diagnosis: non-suicidal panic attack, induced by anxiety.

As if in a broken taffy puller, my nerves clawed to stay together with each passing turn. We didn't know how to answer either Marina's or her sister's cry for help.

A few weeks later, Marina sat next to her sister, timing her seizures and logging about ten an hour in the notebook. Her younger sister's once-rare seizures had become uncontrolled and frequent since Marina started seventh grade. What had once freaked us out had become the norm.

Then, two days before Christmas, we faced the unexpected, the unimaginable. The hospital explained the dire prognosis for Marina's sister, and we made the grueling decision to forego life-saving measures. We relayed our reasons to Marina. Her sister died Christmas morning.

Before New Year's Marina developed gastric pains in the middle of the night. Our grief too raw, we wanted Marina to wait until morning to see the pediatrician. She accused me of not caring about her.

Not cool mom.

We went back to the same hospital where her sister died. The ER doctor found nothing. A slew of GI tests found nothing. The pediatrician again suggested counseling. Her father cajoled and prodded her to go to grief counseling. Lost in my own grief, my steely glare said get in the car now, and we left. She didn't relate to group sessions for children who had lost siblings and refused to go again. My husband reluctantly agreed.

We adapted to Marina's moods. In the morning, we didn't speak to her until she spoke first. Otherwise, sheo growl and snarl. Homework took a back seat. We asked her to attend weekly individual counseling. She refused.

That spring she requested to volunteer at an overnight summer camp for six weeks. We agreed with the caveat she attend weekly counseling.

We interviewed therapists. She rejected all of them, one for taking notes in her presence. Another for being too demonstrative-putting a compassionate hand on her shoulder. Eventually, we interviewed a counselor as a family. What Marina saw as too happy, we saw as upbeat. Marina said she looked like a hippie. We just saw a loose blouse. I made the decision to go with Loose Blouse, and Marina started counseling-and resented me for it.

Not cool mom.

I believed Marina and I had built a strong relationship when she was younger and hoped we could find it and rebuild it, stronger. First part of summer, she began volunteering at the Easter Seals camp. But she left after just three weeks, suffering from intense gastric pains. They cleared once she was home.

At the end of summer, we camped in our RV along the Lake Michigan coastline, Sheboygan to Mackinac Island. Nothing I did pleased Marina. At home, I could walk away from her nastiness, but in the RV, I was trapped.

While traveling, my cousin called and told me her mother was on a ventilator. My aunt chose to disconnect life support and she died. Marina was angry that my aunt would "choose death" -the way "you did for my sister:'

That stopped me cold.

I told her I didn't choose for her sister to die. I explained that her sister had numerous complications and a ventilator would have added one more. We couldn't stop her suffering-we had to be strong and let her go. I couldn't tell if she accepted my explanation.

Sophomore year started, and Marina shared with me what happened her first day at school. I looked around. Was she talking to me? She continued seeing Loose Blouse. Her grief and depression hadn't disappeared; she stayed in her room and spoke to me only when she wanted something. But she began a job as a respite worker with two special needs boys. She took them to football games, the movies, and their special recreation activities. It gave her an outlet for her nurturing nature that I knew was still in there somewhere.

Senior year Marina studied Psychology and recognized what two years with Loose Blouse hadn't made clear: that she was depressed. Marina said she thought she needed medication, but a psychiatrist didn't agree. Instead, he told her she needed to deal with her grief.

Marina and I attended a lecture in early November: Surviving the Holidays after a Loss of a Child. Marina pointed to the presenter and said, "I want to see her” At her next session with Loose Blouse, she told her it was their last session. I scrambled to schedule an appointment with the presenter. Marina faithfully attended sessions with her new therapist and rescheduled when she had a conflict. She even related to me how the counselor was helping her.

It dawned on me that Marina's grief resembled the grief of losing a child. Over summer break, I invited her to meet with my monthly support group of parents who had lost special needs children.

Later that summer, her father and I came home early from a wedding. At the kitchen table, sitting with a girlfriend, Marina's eyes suddenly rolled back, her body stiffened. The girlfriend admitted Marina had smoked too much pot. "It was her first time” she said. I grabbed the phone and passed it to her.

"Call your mother to pick you up” I demanded. "Either you tell your mother what happened-or I will”

For the next several hours, we sat with Marina on the couch, soothing her paranoia and batting away her hallucinations. This was a punishment worse than grounding her. She vowed never to do it again. We had bought Marina a spunky used Honda CRV for high school graduation. Her father kept the car instead.

Almost cool mom.

We purchased a home in Florida and flew back to move Marina into her Wisconsin dorm the next week. College gave Marina her independence-and distance from me. When her poems were published in the university periodical, I flew three hours on a plane then drove two hours to hear her read for five minutes. We flew back for Family Weekend. I took her and her college friends to dinner on her birthday.

Cool mom.

Second semester, her grades dropped. She lied about heavy drinking and casual drug use. Evidence posted on Facebook.

We drew up a contract that stated she would use her savings from high school jobs to pay for sophomore year first semester, and we would reimburse her based on the grades she earned.

The partying continued. However, her grades improved.

She used up her savings.

Not cool mom.

We continued to pay.

Cool mom.

Junior year, she changed schools.

She changed majors.

She moved closer to us.

I wanted her to graduate more than she did. I changed the incentive, dangling a convertible Mustang for a 3.75 cumulative GPA upon graduation. First semester: 4.0. She told us her continued success wasn't about the car but the pride she felt on achieving her goal.

I held my breath.

She shared an apartment with piggy roommates and cleaned up after them instead of them cleaning up after her. She grocery shopped and prepared her own meals. She planned her social life around school, not the other way around. I reminded her about getting the flu shot. She already had.

An adultier adult was emerging.

Senior year she invited me to spend the weekend with her in her apartment in Miami.

We saw Lion King, the musical, and had dinner at KiKi on the River. We toured Wynwood to see the murals on the buildings. We danced at the drum circle on the beach under a full moon. She took me clubbing. I said I wanted to be home by midnight. The clubs opened at midnight. She brushed mascara on my lashes. She glossed red, red lipstick on my lips. She dressed me in her little white cocktail dress. She slipped five-inch heels on my feet. She introduced me to her friends. I smiled as I stomached the stench of cigarettes and hookah smoke. We danced until five.

She posted it on social media.

She shared her life with me.

Marinas face smashed into her pillow, body sprawled on the full-size bed—she had left me a sliver. My stomach grumbled at nine o'clock. I had rejected her idea to stop at Taco Bell at six in the morning. From the common fridge, I grabbed an orange. I sat on the resin chair on her ninth-floor balcony, facing east with a bare trace of the Atlantic visible. A smug smile crossed my face. I had spent the weekend with a decent, compassionate, independent human being.

Indispensable mom. Cool.